Ignácio de Loyola Brandão: the troubadour of Araraquara, a giant and kind soul

Just like Exu, who opens paths and turns crossroads into opportunities, a writer is a guardian of stories.

Ignácio de Loyola Brandão is a modern troubadour who has captured the essence of Araraquara, a city in São Paulo’s countryside, and Brazil itself throughout a career marked by achievements and recognition. While few in the 1950s could have imagined that the son of a railway worker and a housewife—who once watched the dances at the Araraquarense Club with fascination, unable to enter—would become the greatest citizen and chronicler of his hometown, perhaps Ignácio himself always knew.

With his irony and sharp insight, Ignácio became one of the most celebrated names in Brazilian literature, and the world quickly recognized the magnitude of his work. Over decades, he wrote everything from children’s books to novels, memoirs, and major journalistic works, all while maintaining a unique bond with Araraquara. He returns to his hometown with love and respect, and in turn, the city honors him with countless accolades.

That’s why being chosen by Ignácio as the honored author of this year’s Morada do Sol Literary Festival (Flisol) is a privilege that goes beyond the ordinary, immersing me in memories of gratitude and peace alongside my dear friend.

I also extend my compliments to Bernardete Passos, Flisol’s director, for her remarkable work in promoting the city’s culture.

The festival, now in its third edition, previously honored Zé Celso and Mário de Andrade, two icons of Brazilian culture with roots in this land. Zé Celso, a transformative figure in Brazilian theater, was born in Araraquara and was Ignácio’s childhood friend. Meanwhile, Mário de Andrade wrote his classic Macunaíma in the Morada do Sol.

Being remembered would have been an honor in itself, but Flisol went further. Throughout the year, students from public schools in Araraquara, Matão, and neighboring towns read my works and wrote letters to me, inspired by Letters to My Grandmother.

The meeting with these students took place the day after a panel at Casa Afro Brasil, a space dedicated to honoring Brazilian ancestry. This venue was born from the mobilization of the local Black movement, which also organizes one of Brazil’s oldest street festivals.

The Baile do Carmo, a traditional celebration dating back to the 19th century, began on July 16, 1888, when an enslaved man named Damião gathered his people to sing and perform the ancestral Dance of the Umbigada. My thanks go to Professor Valquíria Tenório for teaching me about this historic event.

During our stay at the beautifully restored Municipal Hotel near Matriz Square, Ignácio continued the generous conversations we’ve been having through emails over the years. The first time he wrote about me was for my induction into the Paulista Academy of Letters, where we are fellow members.

When I saw his words, I was overwhelmed with happiness. Later, we had dinner in Ribeirão Preto while attending the Book Fair, and our friendship blossomed from there.

Since then, as I walk to the university where I teach in New York, I often think about the next email we’ll exchange. I recall how excited he was when I told him I would be teaching in the United States. “Go, Djamila, swallow and vomit New York,” he wrote.

I wonder if Ignácio knew about Exu’s itã, in which the orixá swallowed everything in the world only to vomit it back, giving meaning to all things. Exu is the orixá of communication, and only through him can we access the other orixás.

Last week, in our conversations, Ignácio revisited stories involving Lygia Fagundes Telles, Clarice Lispector, Jorge Amado, and Carolina Maria de Jesus, sharing details that brought these figures to life as if they were part of our dialogue.

He reminded me of Exu, who can strike a bird yesterday with the stone he throws today, reflecting his ability to move seamlessly between past, present, and future.

Like Exu, who opens paths and turns crossroads into opportunities, Ignácio is also a messenger and a guardian of stories—a chronicler who transcends the limits of time. His narratives resurrect figures, tales, and episodes with a skill that infuses them with a sense of eternity.

I had the honor of receiving an early copy of the book he’s writing for his granddaughter Antônia, a beautiful gesture connecting generations, filled with love and hope for the future. His friendship is a gift, and his tribute is deeply moving.

Ignácio is a giant, yet a man of simple gestures, kind, and uniquely open to others. How fortunate we are to share this time with such greatness.

Originally published in the Folha de S. Paulo Column

Related articles

November 29, 2024

Djamila Ribeiro hosts Nadia Yala Kisukidi in a public lecture at NYU

December 21, 2022

Djamila Ribeiro launches new website

December 21, 2022

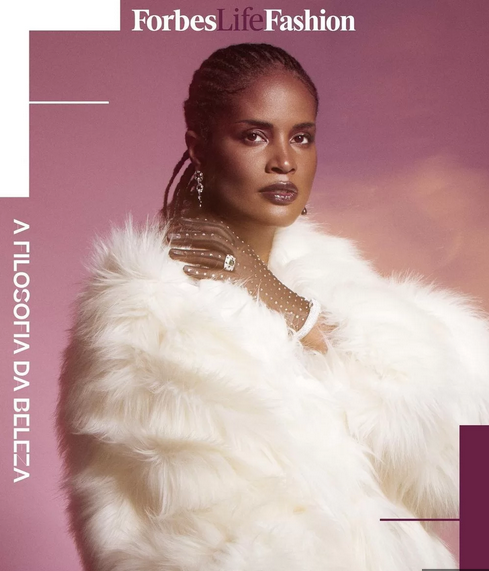

Djamila Ribeiro is on the cover of Forbes Life